The state’s 1960 blueprint for higher education is elitist and woefully outdated. It needs to be updated to reflect how the community college system has evolved.

Dr. Carlos O. Cortez is chancellor of the San Diego Community College District.

Amy Costa, incoming president of the California Community Colleges Board of Governors, aptly described the state’s master ” last month as “antiquated at best.” Community colleges are facing serious challenges securing baccalaureate degree programs, and the 62-year-old governing document is a major reason why.

The plan needs to be reworked not only to reflect new workforce realities, but to eliminate the vestiges of elitism baked into it.

Officially known as the the state’s blueprint for higher education was touted as bringing a collection of competing colleges and universities into a coherent system. The University of California, California State University and California’s junior colleges were each assigned a specific role with a specific cadre of students – all in the name of providing access to higher education for anyone who wanted to pursue their studies.

But the UC system was given outsized influence in the plan’s development. Only the best and brightest students, which at the time came predominantly from the privileged class, would be allowed to attend the prestigious university. Lesser students were funneled into the CSU system, while everyone else only had the option of attending a junior college.

Higher education has evolved over the past 60 years. It is imperative that California stops looking for guidance on how to administer it from a law that was written when Dwight Eisenhower was in the White House. Community colleges today are offering more noncredit, short-term vocational certifications, and public universities offer certifications through burgeoning extension programs. Every college is expected to provide students with more social support, offering resources such as food pantries, housing assistance, legal aid and child care.

In 2014, California took an important step with and a pilot program that allowed 15 of California’s 116 community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees for the first time (albeit limited to career-specific areas in regions lacking skilled labor). That was followed up on last year with which allowed as many as 30 additional community college baccalaureate programs annually.

The results have been impressive. An by UC Davis found that 56% of students graduating from a California community college baccalaureate program said they would not have pursued a bachelor’s degree unless it had been offered there. Community colleges are notably providing in-demand baccalaureate programs in fields the CSU and UC systems overlook.

Another factor: students from disadvantaged families who can’t afford to leave their hometown to attend a university can now secure a bachelor’s degree from a California community college for a fraction of the cost needed to fund a bachelor’s degree from a UC, CSU or private school.

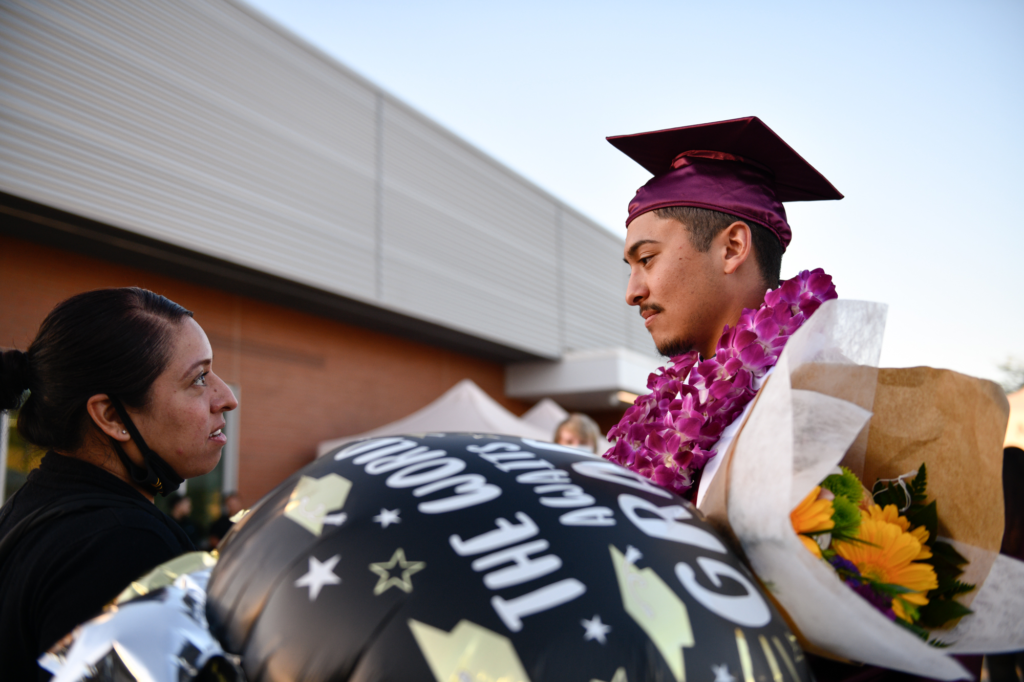

Expanding opportunities at community colleges is a matter of equity. Approximately of community college baccalaureate students are students of color,of community college students are nonwhite, and 35% are the first in their families to attend college. What’s more, California’s public universities for bachelor’s degrees, and are turning away students solely because they have no room.

California’s community colleges are the bedrock of the state’s higher education system. With 1.8 million students at 116 colleges, it is the of workforce training and higher education in the nation. Community colleges are every bit as vital to our economy as the University of California and California State University, and it’s time the governing documents for higher education reflected that.