California

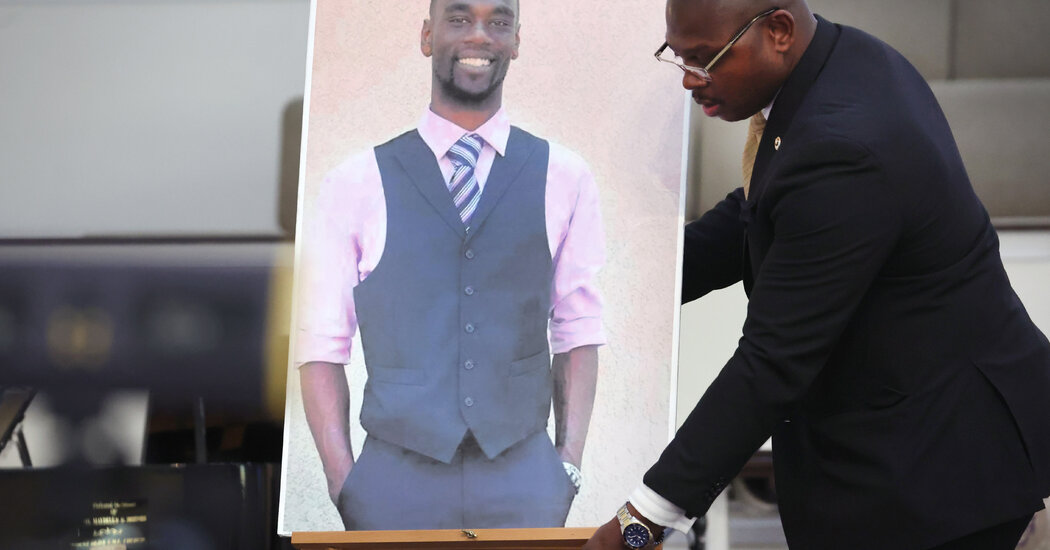

Who Was Tyre Nichols? From Sacramento to Memphis, He Cut His Own Path

Before Tyre Nichols moved to Memphis — before he was brutally beaten on a Saturday night by police officers there — he lived in California, in the Sacramento area, where he hung out with a crowd of skateboarders.

They were a pack of teenage nonconformists. “Our friend group, we were a bunch of little rebels,” said Angelina Paxton, one of Mr. Nichols’s closest friends in Sacramento. But Mr. Nichols, she said, tended to be the voice warning them away from confrontation and serious trouble.

“If anything, he was the one in the back saying, ‘Come on, guys,’” Ms. Paxton recalled. “He was chill. He was peaceful. He was laid back.”

Mr. Nichols, she also said, was wary, as a Black man, of the police. His social media posts show that he identified with the Black Lives Matter movement and harbored a mistrust of prevailing government and economic systems.

And yet recently, Ms. Paxton said, Mr. Nichols had considered becoming a police officer.

“He was talking about how maybe that would be the easiest way to change things in the system — by becoming the system,” she said.

Mr. Nichols, 29, died in a Memphis hospital on Jan. 10, three days after he was pulled over on suspicion of reckless driving. He had fled from the officers on foot, and had apparently been running toward the home of his mother and stepfather, where he had been living.

“All my son was trying to do was get home,” his mother, RowVaughn Wells, said at a news conference earlier this week. “He was two minutes from the house when they murdered him.”

Mr. Nichols’s traumatic death has shocked Memphis, and forced the capital of the old Southern Cotton Belt to reckon with a nightmare scenario that does not fit neatly into most narratives of racist violence: all five of the officers, who have been fired and indicted for crimes including second-degree murder, are Black. So is the Memphis police chief, Cerelyn J. Davis, who this week called the officers’ actions “heinous, reckless and inhumane.”

Mr. Nichols’s life story also cut against old narratives of African American migration patterns. Decades ago, Black people left the former Confederate states in large numbers, headed for places like California in search of opportunity and the hope of greater freedom.

But for Mr. Nichols, it was California, and its high cost of living, that had begun to feel oppressive. In early 2020, Ms. Paxton said, he set out for Tennessee to find a way to make ends meet, becoming part of what scholars have called a “New Great Migration” of Black Americans back to the states of the old Confederacy.

“At least things are affordable here,” Mr. Nichols wrote in a 2021 Facebook post. “OK jobs with decent pay. Cheaper registration fees. Cigarettes that aren’t $10 a pack lol.”

Ms. Paxton, 28, met Mr. Nichols when they were teenagers. They were both involved with a California youth ministry called Flipt 180. “They were trying to give teenagers an outlet that wasn’t the streets,” she said.

She recalled how she first bonded with him in a car as they headed to a church event. She noticed that they were both wearing shocking shades of lime green. She found him to be mellow, but difficult to pin down. When he played D.J. for his friends, he played everything: country music, the rappers Lupe Fiasco and Tupac, reggae.

As they grew closer, Ms. Paxton learned that her friend’s situation was complicated. He had been living with his father in Sacramento, but the father was terminally ill, and would die before Mr. Nichols was out of high school. His mother was 1,800 miles away, in Memphis. Skateboarding offered an escape.

“He was going through a lot,” Ms. Paxton said. “When he skated, it’s like he wasn’t worried anymore. It was like nothing mattered more than when he landed that trick, you know?”

Sometime after his father died, Mr. Nichols moved in with the family of a close friend. After high school, Ms. Paxton said, he bounced around from job to job. He had a son with a woman he was in a relationship with for awhile. Pressure to move up the economic ladder was mounting.

At a certain point, Ms. Paxton said, “he spent most of the time trying to figure out what he was going to do with his life.”

His move to Memphis in 2020 roughly coincided with the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic and its lockdowns. He posted online about missing California, his old friends and his son: on the child’s fourth birthday, Mr. Nichols bought cupcakes in his honor, but acknowledged that he would be eating them himself.

Yet on other occasions, he celebrated the fact that he had escaped to Tennessee.

“He felt the presence of the creator out in Memphis more than he ever had,” Ms. Paxton said. “I mean, the nature, the people are kind — it’s just a whole different world.”

Mr. Nichols was an avid amateur photographer, and his love of his new home was reflected on his Wix page, where he posted images of blues clubs, local landmarks and the sun setting over the Mississippi River. “He liked to go and watch the sunset and take pictures,” his mother said at a news conference in Memphis on Friday. “That was his thing.”

His embrace of Tennessee was also evident from his Facebook entries. In August 2021, he posted a video of himself in a checkered shirt, ball cap and mirrored sunglasses, dancing against a backdrop of farmland to Jason Aldean’s “Girl Like You.”

His other posts offered a glimpse into his passions and his politics. He posted about pro football and basketball. He wrote passionately about the plight of Indigenous people and the resilience of African Americans in the face of centuries of oppression. He denounced modern-day racism, political corruption and the power of elites. He embraced conspiracy theories about chemtrails, the John F. Kennedy assassination and the AIDS epidemic.

In June 2020, the month after George Floyd’s murder, he posted a drawing based on a famous photo of Malcolm X peering out of a window, armed with a rifle. Beneath it was a caption: “Because I have a Black son,” it said, followed by a drawing of a heart. That same month, in a separate post, Mr. Nichols wrote that he had seen “a lot more cops” who had decided to “kneel with all the protesters” and walk alongside them “with no batons and forceful weapons.”

“Humanity is SLOWLY being restored!” he wrote.

Eventually his stepfather, Rodney Wells, helped him find a job at FedEx. The company’s headquarters are in Memphis, and it has long been viewed as a crucial engine for economic sustenance and mobility for Black residents across the economic spectrum. “Those jobs are like post office jobs back in the day,” said State Representative Joe Towns Jr., who represents part of Memphis. “Everybody wants one.”

He worked the evening shift, and would come home with his stepfather, who worked the same shift, at around 7 p.m., when his mother had home cooking waiting. Ms. Paxton said that Mr. Nichols had specific goals: to earn enough to buy a car and a house, and to be able to fly his son out to visit him. Weekends, he would skate and take photos.

On the Saturday night when he was beaten, his mother had planned to cook him sesame chicken, a favorite. When the police stopped him, she said, he was driving back from Shelby Farms, a 4,500-acre park in the heart of Memphis, where he had probably taken in the sunset.

According to an initial police statement, the officers stopped him at 8:30 p.m., and a confrontation followed. He fled, but they chased him and caught him. The statement did not mention the beating, but it did note that he complained of shortness of breath. An ambulance came and took him to the hospital in what the police described as “critical condition.”

At a news conference on Monday, Ms. Wells acknowledged that it seemed like every mother in her position describes their child as good. “But my son, he actually was a good boy,” she said. Ben Crump, a lawyer for the family, noted that Mr. Nichols suffered from Crohn’s disease, and as a result was almost impossibly slim: six-foot-three and 145 pounds.

On Tuesday, one of Mr. Nichols’s three surviving siblings, Jamal Dupree, posted to Facebook a photo of Mr. Nichols as he lay in a hospital bed with a tube in his mouth, his face swollen and bruised and resting on a bloody pillow.

In a later post, Mr. Dupree addressed his younger brother directly: “I’m sorry I wasn’t there to protect you,” it said.

It was accompanied by a video shot from above the cloud line, with a blazing sun on the horizon that appeared.